Locked down and locked out - Holy Week under the shadow of coronavirus

Some suggest that we don't really need to be in church to be the Church, and that receiving the Sacraments physically is something extra as God can give us the grace whether we take them physically or not. Here I want to argue that in Christianity 'matter matters' and no more so than in the way we pray. While we might of necessity for the common good be locked out of our churches this Holy Week that is no excuse for not worshipping with our eyes and our bodies. Indeed, it's absolutely vital we do so and the bishops need to be taking a lead on this.

I think that many of us feel somewhat bereaved at being deprived of our lives beyond our front door, and for those among us who are Christians that is particularly acute because we really miss being able to visit our churches or cathedrals. Quite rightly we need to make this sacrifice, to ensure that this dreadful virus has less chance to spread and to spread less rapidly, in order to save lives and enable the infrastructure of the health service to adapt to these unprecedented demands being made upon it.

However, that having been said being deprived of our churches is not to be underestimated in terms of its impact upon our spiritual wellbeing. Some people are almost happy that people have to give up being in church and receiving the Sacraments, chiding those who feel its loss acutely as having a superficial faith that doesn’t root itself in the knowledge that God is everywhere, and that He doesn’t need Sacraments etc in order to impart grace.

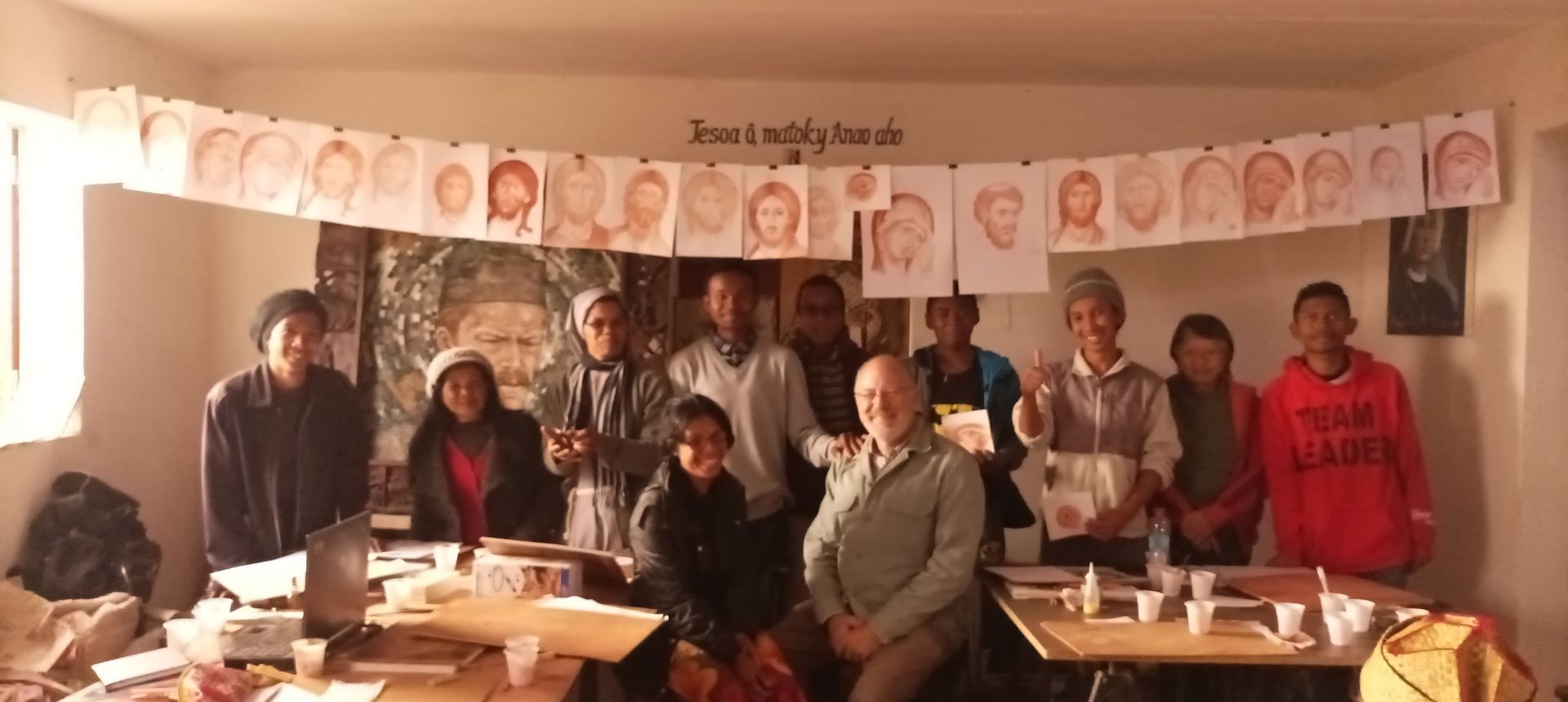

I am a liturgical artist, that’s my job, I would say my vocation. As such I spend my life making beautiful images to grace churches as part of the physical dimension of the celebration of Christian liturgy, and some of these assumptions hit near to the bone for me. It is a reminder that very few people in the Western churches have the faintest idea about just how important physical space and matter are as far as a healthy Christian spiritual life is concerned. In fact I would go so far as to say that those so keen to dispense with the material expression of our faith are the ones with a shallow grasp of what Christian faith really is.

Let me explain what I mean, as that last sentence might appear to some as rather arrogant and offensive. I don’t say it lightly, and I beg your indulgence as I tease out what I mean by that.

A millennia ago the conversion of the Rus is related primarily to the experience the envoys of Prince Vladimir had in the vast cathedral of Hagia Sophia in what was then called Constantinople. Mesmerised by the sheer transcendent experience of the liturgy in that most exquisite of ecclesial spaces they believed that they had somehow entered heaven in a way that no other liturgical or religious experience had managed to do. For the Orthodox of the east the material aspects of Christianity, that is the liturgy, the sacraments, the rites and rituals that accompany the Christian’s life and death, are not some sort of add on to the ‘real’ thing, the ‘spiritual’. In fact the duality behind juxtaposing ‘material’ with ‘spiritual’ is anathema to them as indeed it is to all Christianity rooted as it is in the belief in the incarnation.

The incarnation is the Christian understanding (dogma) that the Word, who is God, became flesh and lived as one of us. God was no longer other to matter and the physical cosmos but had himself entered into it and taken it to himself. That God, He Who Is, He Who is Without circumscription, should be found as a part of his creation is baffling philosophically as a sort of juxtaposition of opposites, something offensive to Jew and Muslim alike, but it stands as the definitive dogma of the Christian faith as definitive of our understanding of who Jesus is, and the purpose of his life and death on earth. As the New Testament explains, “All was made through him and for him. He is before all and holds all things together in him” (Col.1:16-17), and “ God has made known to us his mysterious deign, in accordance with his loving-kindness in Christ. In him and under him God wanted to unite, when the fullness of time had come, everything in heaven and on earth” (Ephesians 1:9-10).

In fact this intimacy between God and matter, between God and Creation has many hints in the Old Testament. God walks in the Garden of Eden as the friend of the first Man, Adam. God manifests himself in material ways, as a group of angels to Abraham, as a burning bush that speaks his name to Moses, as the silence witnessed by Elijah at the mouth of the cave on the side of Mt Horeb, and as majestic visions to various prophets. In the life of Jesus this is taken to a new level with such events as the Transfiguration when Jesus is changed into a figure of light and flanked by heavenly figures. These are what we call theophanies, manifestations of God in physical, material ways almost always associated in some way with Light.

With the conception of the Word in the womb of the Virgin Mary things however are taken to another level. God takes matter, flesh and blood to himself in the most personal of ways and for all time matter now matters as never before. It is not just that God’s presence is found in nature, but that nature is found in God. Matter, matters.

Thus it is not surprising that as Christian life developed it has had a profound relationship to the physical world, shaping it and liberating it in quite mind-blowing ways. At the Last Supper Jesus took bread and made it into his flesh, and made wine into his blood, but not flesh and blood in a earthly limited sense but as the very life of Christ as the Word, the Lord, the Redeemer. It was matter taken up to another level through being fused with the Divine. Thus the Christian cult, that is the way in which faith is expressed as prayer and as something communal, has been rooted in the taking of material things and transforming them into the stuff of heaven. Bread, wine, water, oil, the human body itself, even sexual intercourse all opened up to being vehicles of heavenly power to bring about the transformation of human life from everything that smacks of death, sadness, brokenness. Life and love become touched in the most concrete of ways. This is the very nexus of Christian life, belief and hence of its prayer.

Leonid Ouspensky, one of the great theologians of the revival of iconography in the Orthodox Church of the 20th century explains the implications of this incarnational faith for how we worship. “ The foundation of the Christian life... is the birth of a new life, an intimate union with God which is essentially fulfilled in the sacrament of the Eucharist. A church, as the place where this sacrament is fulfilled and where men, united and revived, are gathered together, is different from all other paces and buildings”. This is merely an articulation of an understanding consistent, universal and enduring centuries in the Christian mind. For example, St Maximus the Confessor could write in the 7th century, “ Just as in man, the carnal and spiritual principles are united, even though the carnal principle does not absorb the spiritual, nor does the spiritual principle absorb the carnal into itself but rather spiritualises it, so that the body itself becomes an expression of the spirit, so also in a church the sanctuary and the nave communicate: the sanctuary enlightens and guides the nave, which becomes its visible expression. Such a relationship restores the normal order of the universe, which had been destroyed by the fall of man. Thus it re-establishes what had been in paradise and what will be in the Kingdom of God.”

The church building is not some utilitarian space dispensable and largely secondary to the life of faith. In a very real way it is an integral expression of it and something which cannot be lightly put aside in a Christian’s life.

To bring this down to earth a bit, if you think about the great cathedrals or those ancient village churches, even the most hardened atheist cannot but be touched by something special about them. Its not really their age, or the majesty of their architecture or just their enduring place in the English landscape, though all of these are true. There remains a numinosity, a sense of it being a thin place where heaven seems just a small step away, angels hanging in the air. This is what Christian sacred space evokes and you don;t have to have faith to sense something of it. Its very real, tangible and precious in its sublime beauty. It is the sort of beauty that makes life far more than existence.

To draw out what I am getting at think of visiting a house when house hunting. Places often have an atmosphere, it might be good, bad, uneasy, peaceful. Somehow places take an imprint of what takes place there and we can sense it, some it must be admitted perhaps more than others. There is far more to spaces than meets the eye, and our interaction with space is something more than use or abuse. Space that has been set aside for Christian use, that has been consecrated for use for prayer, becomes imbued with that coming close of heaven to earth to the point that it ‘hangs in the air’ even when words, music, ritual have ceased.

As a liturgical artist i seek to paint images, known as icons, to enhance these special spaces and to draw out this significance, enabling people to pray with their eyes and their souls to be caressed by grace-filled images. In many churches icons radiate as thin spaces within thin spaces, not so much windows into heaven but doorways from heaven. Heaven breaks through in some sort of sensual, tangible way caressing our whole person, body, soul and spirit. Its a complete, holistic experience of the Divine which has profound implications. It places God in the world and not above or removed or remote from it. This intimacy provides the impetus for the Christian’s work for social justice, for the dignity of every human person, for the important of providing food for the hungry, shelter for the homeless, refugee from those fleeing violence and war, defending the life of the smallest unborn child. Strip away this material context and Christianity is nothing, nothing at all. As St Ireneaus said, that which is not assumed is not healed.

Therefore, when we think about being excluded from these sacred, consecrated ‘thin spaces’ its a very healthy instinct to rebel against this. They touch us in ways even more fundamental than food and drink, and while God is certainly not limited to these humble means, they are the means he chooses to show, express and embody his love for us because it is as material beings, not dismembered spirits, that he has made us. Its like a mother unable to hug her young child as he lies on a hospital gurney dying of the virus. Its that deep, and we are foolish to minimise both the hurt and the impact.

Part of surviving this pandemic is ensuring that we remain as healthy as possible. We take exercise, even if for short walks, or home made gyms. Even I am doing my little exercise routine! The material aspects of our spiritual welfare is just as important, indeed I would argue more so. God is not some remote emotion buried in secret within my metaphorical heart. The Church is not some invisible thing that floats in the air. Or at least thats not the case for Catholics and Orthodox. Protestants might see things a bit differently. But for most of us the Church is a material reality whose absence we feel keenly and the lack of which threatens long term spiritual harm.

That’s a big claim, so let me explore this a bit further. As human persons we are complete and entire, not a duality between body and spirit. There has always been a temptation among Christians to succumb to some sort of dualism, with devastating consequences such as Albigensianism or those in Paul’s time who believed that as they were saved spiritually they could do whatever they wanted materially. Matter didn’t matter, so do as you want.

A long term exposure to a materially minimalist form of Christian liturgical life will corrode the ways in which we as human beings, made of matter, experience God in the fullness of our humanity. Prayer is not just words in a book, its not just sitting still and closing our eyes, in fact it is very little of that. Prayer in Christian terms is something complete and holistic involving all our senses and binding us to one another physically and to the created order around us. A religion of disembodied words or ‘consciousness’ is a religion of gradual irrelevance - out of sight, out of mind.

Sure, for a while we can sustain something healthy but it is foolish to underestimate the consequences not least as this lock down is looking likely to last weeks, and for the most vulnerable - which constitute our main age range within church congregations mind you - for three months at the least. We therefore need to get beyond platitude about God doesn’t need sacraments to give us grace and truisms that the church isn’t a building and start something a little more informed and compassionate, as well as realistic about how we pray as Christians.

Part of that should be about re-educating ourselves about the space we live in and the place of some sort of material marker as to our faith. The Orthodox home usually has its icon corner, and many Catholics have a holy picture of some sort somewhere. However, in our secularised age these practices are somewhat embarrassing and awkward when the rest of the household doesn’t share our faith. So we hide our faith away, understandably. We don’t want to impose our faith on others, and we often have no real understanding of just how fundamental praying with our eyes and the rest of our bodies is.

However, we have to balance all of this with our spiritual health, for which it needs to be expressed and nurtured in physical ways, so we can pray with our eyes, our bodies and not just in our heads. God is not just an idea in our minds, but we are in relationship through and in our entire person. We need to think how we can shape some of our physical space as a ‘thin space’, as in some way set apart for sacred use.

It is here that liturgical art (rather than just religious art) has a crucial role to play. Icons are shaped by and expressive of the Church’s liturgy. They aren’t just an expression of personal faith. Its the same comparison between the Scriptures and a collection of homilies. One is something enduring and universal, the latter something particular and personal. There is a place for both, but we shouldn’t confuse or replace one with the other. Icons are deliberately not naturalistic, somewhat abstract in what we might call an ascetical aesthetic. They are not designed to replace the realities they make present, but to melt away so we can connect with the realities reaching out to us through them. They don’t seek to work on our imagination, transporting us somewhere imaginary, but to be conduits in the present moment of spiritual realities that are actual present even if not visible. You could put it that they contain their own irrelevance - ‘Don’t look at me, but to the one I make present!’

Icons come in many different styles, so its not very prescriptive or limiting. Russian ones tend to be very ethereal, Cretan one’s highly stylised and rigid, contemporary English ones more painterly. Just a quick browse on Pininterest and you can find a vast range - though not all are good so it needs careful selection. Educating oneself about what icons are good, and how they function is another good step to take, so you can select and arrange images in a way that opens up a little bit of the church sacred space in your own home. An icon of Jesus, whether Pantocrator or on the Cross or in the arms of Mary should take centre place. Flanking them should be angels, archangels and seraphim, the spiritual powers. Then come prophets and evangelists, our patron saints (personal, local and national). In creating this visual space we are opening the doors of heaven for these saints to come and be a part of our home.

While we cannot physically celebrate the Divine Liturgy as it is usually done in our churches, we can participate in other ways. The Divine Liturgy (the Mass) is an enactment on earth of something taking place in heaven, its reality breaking through from heaven to earth. As it says in the letter to the Hebrews, “But you have come near to Mt. Zion, to the City of the living God, to the heavenly Jerusalem with its innumerable angels. You have come to the solemn feast, the assembly of the first born of God, whose names are written in heaven.”

We can glimpse something of this in the Book of Revelation which some scholars maintain is a description of the Mass as experienced and understood by the early Christians. Whether that is so or not, the understanding of the Church has been well articulated, that what we do on earth in our liturgy is but a shadow of what is taking place in heaven. Our pale shadow enables the worship of the angels and archangels to be opened up for us to participate in, to stand with the whole company of saints, martyrs, confessors etc as they worship our Heavenly Father. While we can’t ourselves celebrate the Mass without a priest, we can allow something of those heavenly realties to nevertheless break through in our homes every time we pray.

This is much more than just listening to the Mass on our iPads or smart phones, good as that is. It is about creating a similar sort of space in our own homes, however small and discrete or elaborate and substantial. Through setting aside a physical space and shaping it with imagery that draws out what is taking place there as we stand before God and pray united with the priest offering the Mass online, we can begin to pray not just in our minds, but with our bodies and with our eyes, something more complete and healthy and more fundamentally connected to one another in physical space. In keeping to the communal actions of our church liturgies, such as making the sign of the Cross, kneeling or standing, blessing ourselves with holy water or kissing icons or touching them, we unite ourselves materially with the whole Christian community as it participates in Christ’s Mysterious Presence in these common rituals. It helps bind us to one another despite the physical distance.

This is going to be acutely important in Holy Week. This is THE liturgical celebration of the Christian year, something which is so holistic and complete as an experience of salvation it is rightly the defining Christian ritual. It takes us liturgically into the realities of the Passion and Resurrection not simply in our memories but in our experience of God in prayer now. What was eternal and enduring breaks through to us, and draws us in, it refreshes our faith, renews our hearts, lances our sins and fills us with the Divine Life. It is a complete ritual spanning an entire week, by consecrating this week we make all weeks holy. Its a way of handing our lives, our time, our thoughts, actions back to God in order that we might ourselves become ‘thin spaces’, like the icons that hang in our homes, and the churches where we normally gather to pray.

We need to think carefully about how we pray. Simply sitting in an armchair is not perhaps sufficient as our only way of worship. Bows, making the sign of the cross, standing and sitting, kneeling all can have a part to play. This is going to be critical during Holy Week because that is the time each year we enter deeply as a community into the great Mystery of our salvation. We need to re-cement the spiritual bonds between us in material ways, not simply slipping into our own individual made up routine, but developing something together, using the common gestures and features which would normally feature in and decorate our churches during this most sacred time. Ideally our bishops would take a lead in this, and not leave it up to individuals and local clergy to muddle through. However, if that is missing then we can at least take the idea seriously, understand that it is important to nurture the physicality of our worship and to create some thin space with icons and so forth as a lynch pin in keeping our spiritual lives alive and incarnational.